One point of contention in the FOR585 Advanced Smartphone Forensic class is – which files store the correct datetime for when a user created an iOS backup? I’ve engaged in a few friendly arguments over this topic and it recently popped up again when Lee was teaching in NYC in August. Every time this question comes up, I test it again. I have probably tested this more times than I should have, which is why I am finally putting it in writing.

So, when you are asked – “When did a user last create an iTunes or iCloud backup?” – You can answer with confidence next time.

The first thing to consider is what you are examining. Are you looking at a backup file extracted from a PC or Mac? Are you looking at an iCloud backup? Are you looking at a file system dump created by a commercial or free tool? If you are looking at a backup (iTunes or iCloud) this process is a lot easier. If you are looking at a file system dump created by a tool, this is where the confusion may set in. I hope this blog makes your examination easier by breaking down what is happening for each file. For this test, I used my own iPhone that I use every day. Why? Because I know when I backup and I can then verify dates.

The files we are going to examine for backup datetime activity include:

- info.plist

- status.plist

- manifest.plist

- device_values.plist

All of these files are important, but the dates inside of each may vary and a smartphone tool may update the date inside of the file. If you are looking at a backup that was extracted from a PC or a Mac, the status.plist will contain the start date and time for an iTunes backup. The info.plist also stores a datetime and whether the backup was successful (snapshot state), but it is not the start date. It is often the completion datetime and doesn’t state if the backup was successful, which is why I rely on the status.plist, when the file is available. The manifest.plist is more helpful when it comes to dealing with locked backup files that need to be cracked. The date in the manifest.plist is often the same as the date in the info.plist and again this file does not track if the backup was successful or not.

Now here is the tricky part. If you completed a file system dump of an iOS device, the following files will most likely show a date that is NOT when the user created a backup. This date will be when you created the forensic image. This makes people uncomfortable, but it makes sense if you think about it. iTunes (or a process like iTunes) is most likely being used in the background to create the forensic image. It makes sense that these datetimes would be trampled. In this case, I rely on device_values.plist which remains untouched by any tool or method you use to create a forensic image of an iOS device.

At this point I have either confused you or validated what you already know. Either way, let’s take a look at my test.

I dumped my iPhone using Cellebrite Physical Analyzer Method 1. I only did Method 1 because I wanted to make sure that it pulled the device_values.plist and I was doing this test during a lab and didn’t have much time. NOTE: I have noticed in the past that this file may only be pulled using Method 2, so use both just in case. If you are wondering why I recommend both of these extraction methods refer to my previous blog posts. I completed this extraction on August 18, 2018 around 14:20 (I had a few connection issues and had to troubleshoot which is why I state “around”). I did not backup my device at this time other than using my tool to create a file system dump (aka – I did not launch iTunes and create a backup).

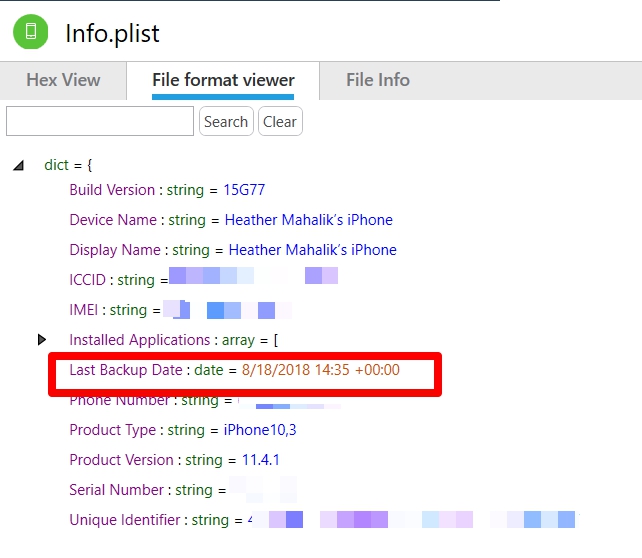

The info.plist is shown below. Notice the timestamp matches the extraction completion time and NOT the time the device was backed up by the user? If you used a commercial tool to acquire the device, simply look at the Extraction details to compare extraction time.

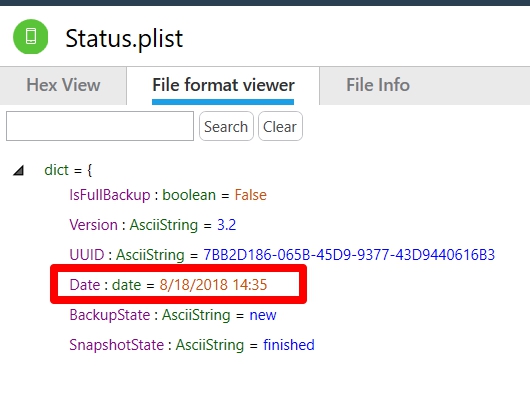

Next, I looked at status.plist. Again the date is NOT when the user backed up the device. This is when the extraction completed in Physical Analyzer.

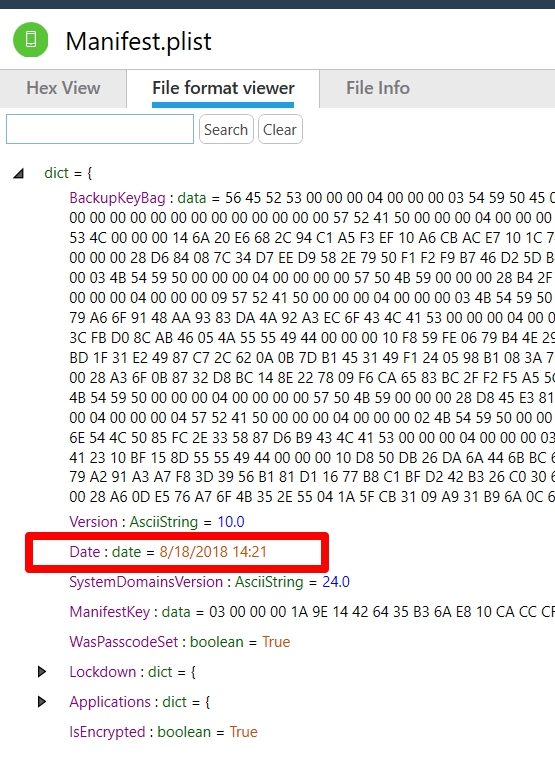

Finally, we look at the manifest.plist. And we see the same date, but a time that occurs before the times in info.plist and status.plist.

I believe this is when Cellebrite scans the phone to determine if the tool should present you with the check box to encrypt the backup, or not, if the device is already encrypted. This is also around the time I started the extraction. So, this is really just showing you how long the Method 1 extraction took and has absolutely nothing to do with when the user last created a backup. Now we look at the device_values.plist and we get the correct answers.

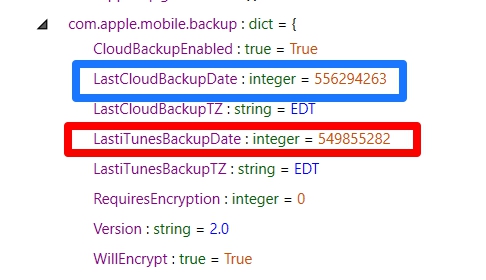

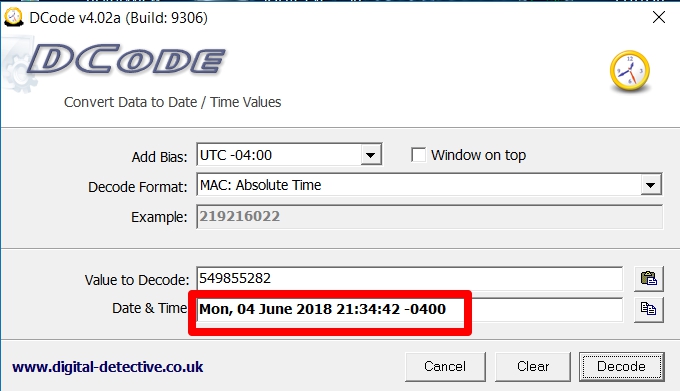

Not only do we get to see datetimes for iTunes backups, but also iCloud, if the user has ever backed up to cloud under com.apple.mobile.backup. We simply have to decode our datetime stamp for the LastiTunesBackupDate and we get June 4, 2018 at 21:32:42 Eastern Time. (Note: I normally keep it at UTC, but I know when I created my last backup in local time and wanted to compare).

So, in short the forensic extraction methods will update the datetime in status.plist, info.plist and manifest.plist during the acquisition process. If you are conducting analysis of an iOS device image (not a backup) you should rely on the datetime recovered from device_values.plist. If you are dealing with a traditional backup file, use the status.plist for the datetime on when the last successful backup was created.